Restoring an old BRIO piece or set, or any vintage or antique toy for that matter, is a fairly controversial topic and you’ll find little agreement among toy collectors about how much restoration work is considered proper, and what impact it will have on the toy’s value. And the more intrusive and potentially risky the work being done, the more controversial it is.

That being said, some restorations are low- or no-risk and result in an original toy with all original components. Done properly, this can result in a part or set that is in better condition that it was originally and that almost always translates to greater sale value. It’s the most advanced type of restoration work, where you are permanently altering original parts, that carries the greatest risk.

I think of restoration work as falling into one of three broad categories depending on the intrusiveness of the work being done, and I describe each below.

Trivial Restorations

A trivial restoration is one that carries no real risk to the piece or set, and does not require any tools.

Typical examples of a trivial restoration would be taking the best parts from two or more sets in order to create one complete set in the best possible condition, using two partial sets to build one complete one, and simple cleaning of parts with a damp rag.

The primary issues with building a set from one or more others are that you must ensure that replacement parts really are identical to the ones being replaced, and that the styling and finish match the other pieces in the set. The latter is a particularly important detail because BRIO was not always consistent in applying gloss finishes or varnish to its parts and you don’t want to mix glossy pieces with matte pieces, or varnished wood with unvarnished wood, in the same set. Similarly, you also need to ensure that the paint hue and varnish tints are consistent, as some ofBRIO’s lacquers did have minor color variations and some of their varnishes did yellow more than others with age.

The basic rule is that all the pieces in the final set should look like they belong together. They should have roughly the same color tone, finish and wear.

You do not need to disclose this sort of restoration work if you coose to sell the restored part or set, but of course the condition that you advertise should be lowest common denominator. If you use a used part to replace a missing one in a new set, then you can’t really claim that the set is new.

Minor Restorations

A minor restoration is one that involves user-replaceable components, or components that can be easily scavenged from identical pieces, and cleaning with a mild detergent solution or solvent. There is typically some risk involved in this type of restoration because detergents and solvents can potentially damage paint finishes and stickers, and some disassembly of the toy may be required and that process can damage it–particularly if the components are held together with non-removable or tamper-proof fasteners, or with permanent adhesives.

The most common reasons for a simple restoration are to remove pencil and ink marks from wood or paint, fix a broken piece, or replace a particularly worn component with one that is in better condition.

As with trivial restorations, you must take care to ensure that your replacement part matches the original in styling, color tone, and finish.

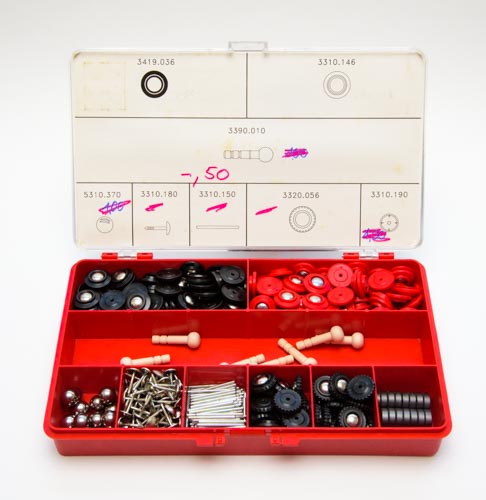

Typically, when you are doing this level of restoration you are not making alterations to the original part, merely replacing worn, damaged or broken parts with manufacturer-original replacements. BRIO even produced repair kits for this exact purpose. In the early 70’s, replacement magnets, plugs for male track connectors, and wheel axels for the rimless wheels were sold separately. In the early 1980’s, they were all combined into a single kit and sold as the #33392 Spare Parts accessory.

BRIO even produced a repair kit for the single-axel, rimmed wheels that debuted in 1986. This kit included magnets, nails, rimmed-wheel axels, red and black wheels for trains, and black treaded tires for vehicles (it also included spare balls for the labyrinth games). This kit appears to have only been sold in Europe.

As with trivial restorations, you do not need to disclose this sort of restoration work so long as you are only using original BRIO parts, either from a repair kit or salvaged from another original BRIO toy.

Major Restorations

Major restorations are the most controversial because they involve permanently altering the original part, or fabricating replacement parts from scratch. While every collector probably has his or her own opinion as to whether or not this sort of action ruins a toy, one thing they will all agree on is that you absolutely must indicate that the toy has been restored if and when you choose to sell it. There are no exceptions to this rule. You need to clearly indicate what work was done, what the source of any replacement parts was, and most importantly, what paints were used–specifically the paint brand, type, and color–so that they can be checked for safety (it should go without saying that you should never use lead-based paints, especially on toys).

Should you do major restoration work? Some collectors prefer that classic or antique toys remain in their original condition even if heavily worn, but some buyers really appreciate the almost-new look of one that has been properly restored. So before you go grab your wood putty and paint supplies, consider what impact your actions might have on its value. If you are restoring a BRIO piece just for your own collection, then of course you have little to lose save for the risks of damage to the piece itself. But if your goal is to try and increase its resale value on the used market, keep in mind that your restoration efforts may have the opposite effect of what you are trying to achieve, even before you figure in the cost of your supplies.

Also keep in mind that using modern chemicals (solvents, paints, etc.) to restore a toy may actually cause long term damage to other parts of it. So major restoration work is not just risky from a financial perspective, it is potentially risky for the toy. Even experts working in museums occasionally make decisions that turn out to be wrong causing damage that is not noticed for several years.

Some examples of major restoration include:

- fabricating replacement parts

- sanding wood with coarse-grit paper (this removes the original finish, if any, and also changes the thickness)

- using harsh solvents to remove stubborn stains and mystery substances

- using polishing agents to restore the shine to metal components

- repainting or refinishing

- altering one part to match the styling of another

- removing dried glue applied by a previous owner

Sometimes the damage to the toy is so severe that you have nothing to lose except maybe your time and some money.

Some ground rules for major restoration work

Even if you don’t plan on reselling your restored BRIO part, you should still follow these basic rules for restoration. If you are going to do it, you should do it right! And besides, you may decide to sell your collection some day and a properly restored part is going to fare better than one that was sloppily done. You also don’t want to create confusion in the collector market by advertising a toy with mix-and-match components as being a valid, original configuration.

- Take pictures of your BRIO toy before you begin. Document, photographically, all important details such as painted surfaces, colors, sticker types and locations (repainting almost always means removing or destroying a sticker), and so on. Save this documentation in printed form and store it with your toy, or somewhere nearby so that you can find it later.

- Document, in writing, everything that you did to restore the toy including any intermediate steps. As with #1, store a hardcopy with or near your BRIO toy.

- Reproduce the original part or finish as closely as possible. Work from photographs or a copy of the original part to ensure accuracy.

- The final toy should have roughly the same condition and wear overall, so if you are going to restore any part of the toy you should commit to restoring the entire piece or set. It makes no sense to have shiny new wheel hubs on a worn and tattered train. A partially restored toy generally looks worse than a worn toy.

- As with other restorations, pay close attention to details such as fasteners, stickers, clear coats and color tone. Your completed part should blend in with the rest of the set.

- When fabricating wooden parts use the same wood as the original toy, which for almost all BRIO components means using beechwood. If you don’t have beechwood or access to it, sacrifice a part that you don’t need and use it for raw materials.

- Use lacquer spray paints for painting wooden parts to best reproduce the finish of the original BRIO lacquer paints. This generally means resorting to the synthetic lacquer sprays used by plastic model hobbyists and sold in home improvement stores since true lacquer paints require powerful solvents that make them impractical and even dangerous to thin and spray by the layperson. True lacquer sprays are also expensive and only come in a limited range of colors.

Restoration advice and resources

The article Restoration Advice and Resources outlines some advice, techniques and additional resources that will be of assistance to you if you plan to take on a minor or major restoration project. You can also read the restoration section of the blog for additional articles of interest as well as examples of my own restoration work.