I spent a little bit of time analyzing the RFID technology behind Smart Track and Smart Tech this week. Smart Tech is BRIO’s current generation of RFID-enabled engines, released in late 2017 in Europe before making its way to the U.S. the following year. Smart Track was first released in 2005, and to my knowledge was not available in the U.S.

Note: Smart Tech Sound, released in late 2020, is a different product line that is more sophisticated than the first generation of Smart Tech.

The first question people ask is:

Are Smart Track and Smart Tech products compatible?

No.

A quick disclaimer: I am not an expert in RFID or digital signal processing. I know enough to talk at a high level, but that is about it.

The reason they are not compatible is that the two technologies use different RFID tags. The older Smart Track appears to use UHF (ultra-high frequency) tags and operates at around 909.033 MHz. The newer Smart Tech operates in the HF (high frequency) band at around 13.56 MHz.

Both are ARPT (Active Reader Passive Tag) systems. The tag reader is in the engine and it transmits an interrogator signal which also provides the power for the tag stored in the track (Smart Track) or tunnel (Smart Tech). The reader in the engine then receives the transmission from the tag and processes the signal.

Smart Track

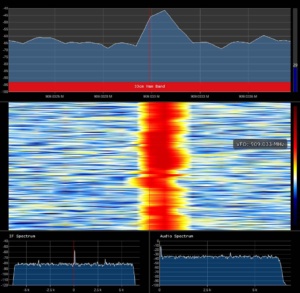

The following waterfall and FFT plot shows the signal sent by the Smart Track engine while in operation.

From the late 1990’s through the early-to-mid 2000’s, UHF tags were fairly popular because they were, and still are, low-power and cheap. The problem with UHF, however, is that there is no single, global standard for radio waves in this band and thus regulations differ from country to country. In North America, the UHF band for RFID runs from from 902-928 MHz, but in Europe that band is between 865 and 868 MHz. As these two bands do not overlap, that means UHF tags made for one market can’t—or shouldn’t—be used in another.

What’s odd about Smart Track is that this is exactly what it seems to be doing: my engine is transmitting in the North America band, despite the fact that it was purchased from a seller in Germany which uses the European band for RFID. That poses an interesting question: are all Smart Track products operating in this North America band? If so, then they may be running afoul of broadcast restrictions when used in Europe. And if not, then there would potentially be a compatibility issue between Smart Track products that were produced for different markets.

I don’t have good tools for analyzing the RFID transmissions in the UHF band, but my best guess is that the tags used by BRIO are very simple and merely indicate what chip is present. The actions, and the sounds produced by the Smart Track engine, are stored in the engine, itself.

Smart Tech

Smart Tech uses the HF band at 13.56 MHz, which is a global standard for RFID. Using special hardware designed to analyze HF and LF tags, I was able to capture the following RFID transmissions.

The first image shows the “Station” tunnel, which tells the Smart Tech engine to stop and play a short sound recording reminiscent of a train station. As you can see, there is not a significant amount of data being transmitted, which implies that all the sounds and actions are stored in the engine.

Compare this to the next image from the “Reverse Engine” tunnel.

There is not a big difference between the two profiles (ignore the difference in the pulse amplitudes). This appears to be a very simple encoding scheme where each pulse represents a bit of data, transmitting about 36 bits total. In the “Station” tag, the transmission starts with 110101111, while the “Reverse” tag begins with 110111110. The trailing 01010101 is probably used for clock synchronization and an “end of data” marker.

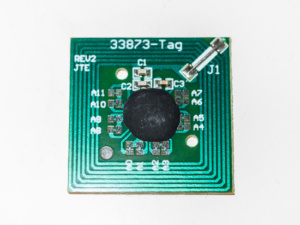

The tag itself has pins A0 through A11, which implies there’s a total of 12 bits that make up the device ID. Simple tags such as these are very common in toys.

What this means

The implication here, for both Smart Tech and Smart Track, is that the complete set of engine behavior and sounds have been predetermined. Since there is no procedure for loading new data into the engine, the full range of products has to be decided upon before the engine programming is completed.

In theory, one could generate the above signals and transmit them to the Smart Tech reader. This procedure could also be used to probe for the full range of behavior supported by the engine.